Oddly, given that more than two-thirds of my life has been lived away from England, in the last few days people have felt compelled to offer their condolences to me on the loss of the queen. And unexpectedly, given my long voluntary exile, it means a lot to me.

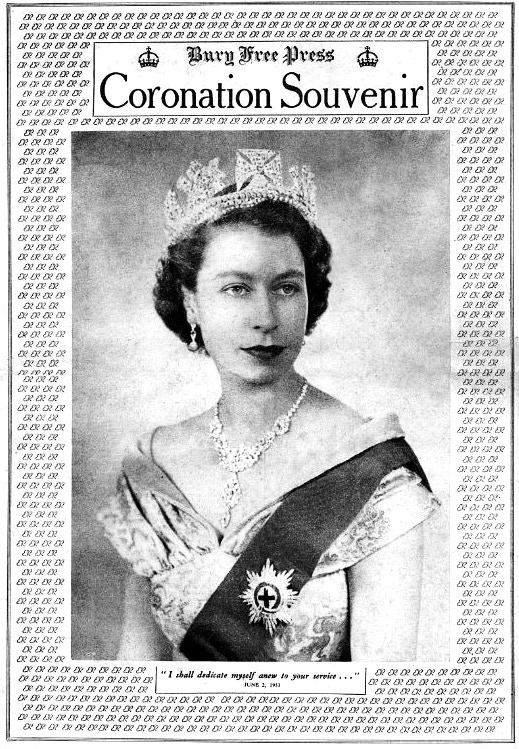

Perhaps this is because she is part of my earliest memories. As a not-quite-5-year-old in June 1953, I was one of the little kids lining the parade route for her coronation. I had a little Union Jack and I was propelled forward through the crowd with the other little kids to sit on the curb between the feet of the policemen supervising the crowds.

Although it was the first televised coronation, we didn’t have a television, nor did anybody we knew. My parents’ generation felt pretty lucky, not so long after World War II, to still have a queen and country to celebrate, so we went up to London by train from our upstairs “cold water” flat in a terraced house in Southfields, about half an hour on the District Line from Westminster.

In the evening, we all turned out for the street party – dining room tables were hauled into the middle of the street, plates were marked with Elastoplast tape and initials on the bottom, cutlery had colored thread tied around it – no plastic in 1953. I distinguished myself by falling down and gashing my knee on a sharp stone in the asphalt – a scar I still have.

I’ve never met the queen (although I have in person saluted her sister, Margaret, as a member of a color guard). Her Majesty never invited me to tea or exchanged a few pleasant words with me in a crowd. But she was, nonetheless, an enduring symbol of my inner life as an English person.

She died as she lived. Doing her duty quietly and without fuss to fulfill a destiny she didn’t choose. To the last, she displayed dignity, warmth and compassion.

And I find myself sadder than I would have expected.