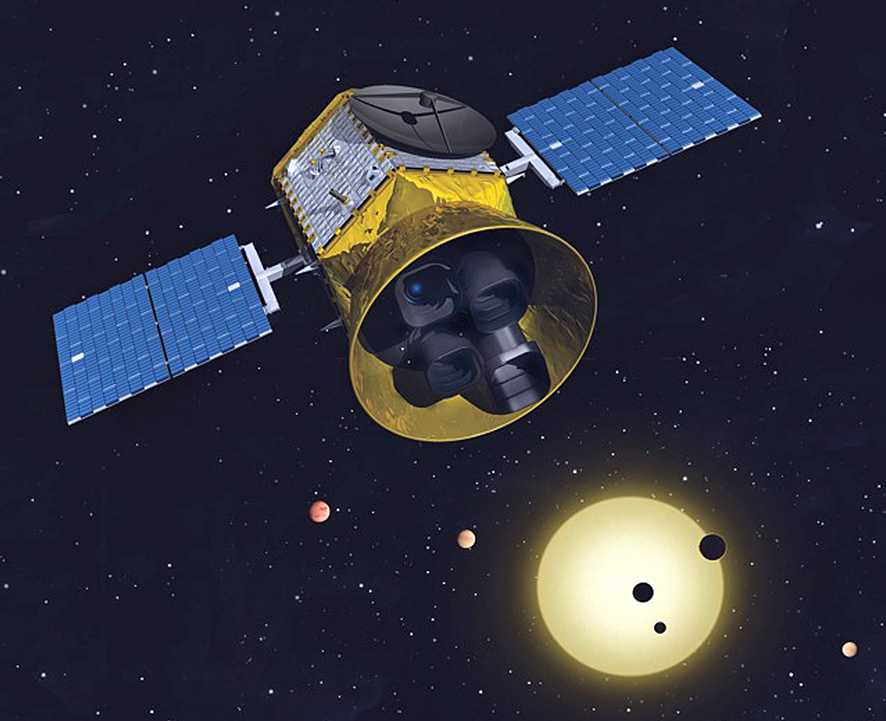

By all accounts, TESS, the planet-hunting satellite, is having a banner year and in doing so is taking work from Greenbelt into distant solar systems. Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite is a NASA mission proposed by Principal Investigator George Ricker and a science team led by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). Greenbelter Padi Boyd is the NASA project scientist for TESS and chief of the Exoplanets and Stellar Astrophysics Laboratory in the Astrophysics Science Division at Goddard Space Flight Center. So far this year, scientists working with TESS data have announced a world orbiting two stars.

This first-of-its-kind find was made by high school student Wulf Cockler who had been a summer intern at Goddard. Cockler started working with the TESS data and examining the variations of star brightness. “About three days into my internship, I saw a signal from a system called TOI 1338. At first I thought it was a stellar eclipse, but the timing was wrong. It turned out to be a planet,” he said.

Alpha Draconis Eclipses

Star gazers have long known that Alpha Draconis, part of the constellation Draco, is a double star. About 4,700 years ago, in ancient Egypt, Alpha Draconis was Earth’s North Star, the star closest to the North Pole. Now, because of Earth’s wobble in its rotation, Polaris is the North Star; however, Alpha Draconis remains a well-known, well-studied star. So it was a great surprise that researchers found something so fundamentally new.

“The first question that comes to mind is ‘how did we miss this?’” said Angela Kochoska, a postdoctoral researcher at Villanova University in Pennsylvania. She presented the findings at the 235th meeting of the American Astronomical Society in Honolulu on January 6. “The eclipses are brief, lasting only six hours, so ground-based observations can easily miss them. And because the star is so bright, it would have quickly saturated detectors on NASA’s Kepler observatory, which would also mask the eclipses.”

An Earth-sized World

The team also found an earth-sized world where conditions might be right to allow liquid water on the planet’s surface.

The planet is orbiting TOI 700, a small dwarf star located in the southern constellation Dorado. The star is about 40 percent of the size of our Sun and about half of its temperature. Originally the TESS database showed TOI 700 the same size as the Sun, but scientists recently corrected the mistake.

“When we corrected the star’s parameters, the sizes of its planets dropped, and we realized the outermost one was about the size of Earth and in the habitable zone,” said Emily Gilbert, a graduate student at the University of Chicago who was one of the presenters of the discovery.

This work is in addition to the comet 46P/Wirtanen study done by University of Maryland scientists presented last year. Their dynamic image shows the comet’s explosive emission of dust, ice and gases during its close approach to Earth in 2018.

All of these discoveries are possible because TESS monitors large swaths of the sky for 27 days at a time. This long view allows the satellite to record changes in stellar brightness, which means researchers see tiny planets orbiting the stars, eclipses and other pieces. And it means researchers have a lot of data to dig into.

After grabbing so much attention in the scientific world, the satellite received more accolades in the general press. The magazine Popular Mechanics named TESS as one of the top 20 machines of the decade.

The research pace is a lot to live up to, but Boyd, who studies exoplanets and binary stars herself, said the best of TESS is yet to come. “[I’m] looking forward to the 2020s, when we will take the next steps,” said Boyd. “We are exiting this decade in a much stronger position and we know how to take the next steps to imaging a ‘pale blue dot’ around another star in the future. Imagine the articles that we will write, and the missions we’ll be looking forward to launching, 10 years from today.”