A grant application to fund a Vision Zero study in Greenbelt was mentioned in the News Review’s April 18 issue in coverage of the city’s budget. At that time staff were preparing for the Vision Zero grant application, “modeled after an international effort to achieve zero fatalities and serious injuries on the roads by 2030.”

Objectives

Vision Zero originated in Sweden, sparked by an accident in 1995 in which five young people died when their car hit the concrete base of a street light after skidding on a turn in rainy weather. The objective of Vision Zero is to eliminate road deaths or serious injuries to both car riders and pedestrians. While this may seem like pie in the sky given the approximately 43,000 U.S. road fatalities in 2021, participating Baltic countries see tantalizing evidence that it’s possible. In 2019, both Helsinki and Oslo (cities of about 1.3 to 1.5 million people) had zero pedestrian fatalities and in Oslo just one driver died. In comparison, Dallas, Texas, also has about 1.3 million people, and between 2016 and 2020 there were 286 pedestrian fatalities, over 70 per year. Greenbelt is tiny in comparison, but has also had its share of fatalities: around three per year.

A New Perspective

The shift in thinking is that it isn’t just drivers who need to step up to safe driving – obey the rules, not drink and drive and so on – it also is the authorities who design and build roads who need to design to minimize the destruction that takes place when drivers or pedestrians blunder. Vision Zero makes the point that in air and train transportation, providers of the infrastructure must obey stringent requirements about the safety built into their infrastructure. Road transportation, however, lays the blame on the users of the transportation system when there are accidents – and barely considers the risk involved in the physical layout of the roads.

Shared Responsibility

Vision Zero, increasingly making impacts across Europe, says that if roads are designed for idealized drivers who don’t make mistakes, then they will be inherently dangerous because it is inevitable that drivers will blunder. It seeks to share responsibility with local authorities, asking that they actively minimize the risks to road users arising from the transportation infrastructure itself – keeping solid objects back from travel lanes, calming traffic, narrowing or removing lanes to dampen speeds and separating different classes of road user.

Swedish authorities focus on strategies that limit damage, addressing solid obstructions close to roads, the hazards and blind spots of pedestrian crossings and the mayhem that results if a vehicle crosses into opposing traffic. While vehicles may have become safer – with safety belts, infant car seats, rollover protection, lane guidance and airbags to name a few advances – the environment they drive in has become, if anything, more dangerous. There are more cars on the road, more traffic lights and intersections and more high-speed roads.

Progress is Uneven

Progress isn’t perfect. In the U.K., for example, an attempt to create a standard 20 mph speed limit in urban and suburban areas caused a ruckus and was derailed. However, research shows that in congested areas, lower speed limits actually result in faster travel times because they reduce traffic snarls and delays resulting from overtaking, stop-start traffic and fender-benders. It’s that old parable of the tortoise and the hare again.

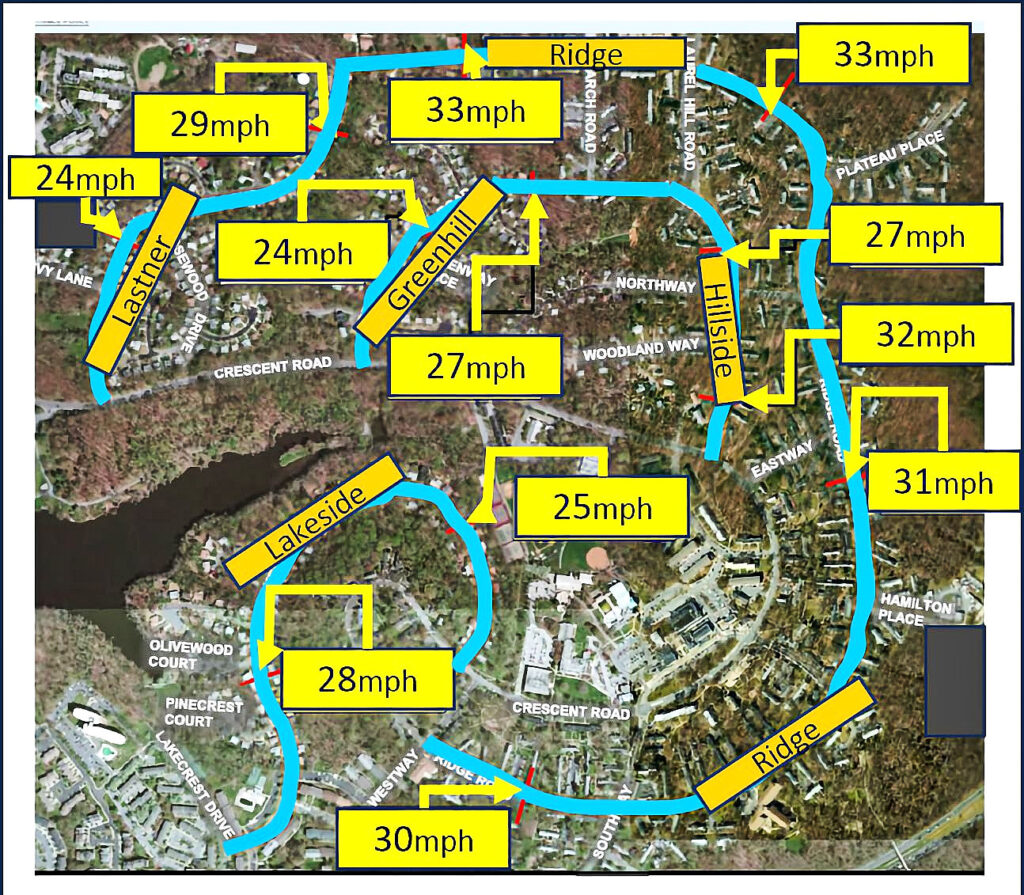

Greenbelt’s Roads

Greenbelt is only responsible for part of its roads, with the county and state both having sovereignty over the more major routes and each authority with its own ideas. Nonetheless, Vision Zero has the potential to increase safety for Greenbelt residents, especially if pursued collaboratively by all stakeholders. At the time of the April 3 budget worksession at which it was discussed, staff were preparing a grant for federal funding of a “Comprehensive Safety Action Plan” that would be Greenbelt’s Vision Zero action plan.

Greenbelt’s Action Plan

Speaking to the News Review, Greenbelt’s Assistant Director of Planning Jaime Fearer said the city has applied for $200,000 in funding and plans to match it with $50,000 if awarded (there is a 20 percent match requirement for the grant). The grant funds would be used for “planning demonstration and supplemental planning.” That means that they will be used to develop the Vision Zero Action Plan for the city and create pilots and demonstrations to inform the planning process. For example, quick build demonstration projects could use strippage, signage and flexible posts, but wouldn’t involve pouring asphalt or a full rebuild of roads.

Another aspect, part of the “supplemental planning,” would be a health equity assessment. The city would like to start looking at transportation and infrastructure through a health equity lens, said Fearer. With the grant they’d begin gathering baseline data to better understand health outcomes of residents across the city and how transportation might impact that. That would include reducing fatalities and injury but also could include questions of mobility and access.

If awarded, the completion of a certified action plan (something required before implementation funds can be applied for) is expected to take about two years, based on averages elsewhere. Informed by data from the planning process, and with the required certified plan, the city might then apply for implementation funds for a full capital project, possibly from the same federal funding source. Fearer notes that it’s a city goal to create a Vision Zero Action Plan. The city expects to hear back about the grant by August but hopes it might be sooner.

A recent article on the BBC.com website gives details about Vision Zero that may be of interest to Greenbelters: bbc.com/future/article/20240517-vision-zero-how-europe-cut-the-number-of-people-dying-on-its-roads.