The movie Blitz, about a young boy in World War II London, currently is on screen at Greenbelt Cinema. Sylvia Lewis may be the only Greenbelter who, as a small child, experienced the Blitz in the East End of London, where the docks and shipyards were a prime target. Lewis’ view of the period as a small child is different from that of an older person, of course, but a letter her mother wrote in October of 1941 provides the viewpoint of an adult.

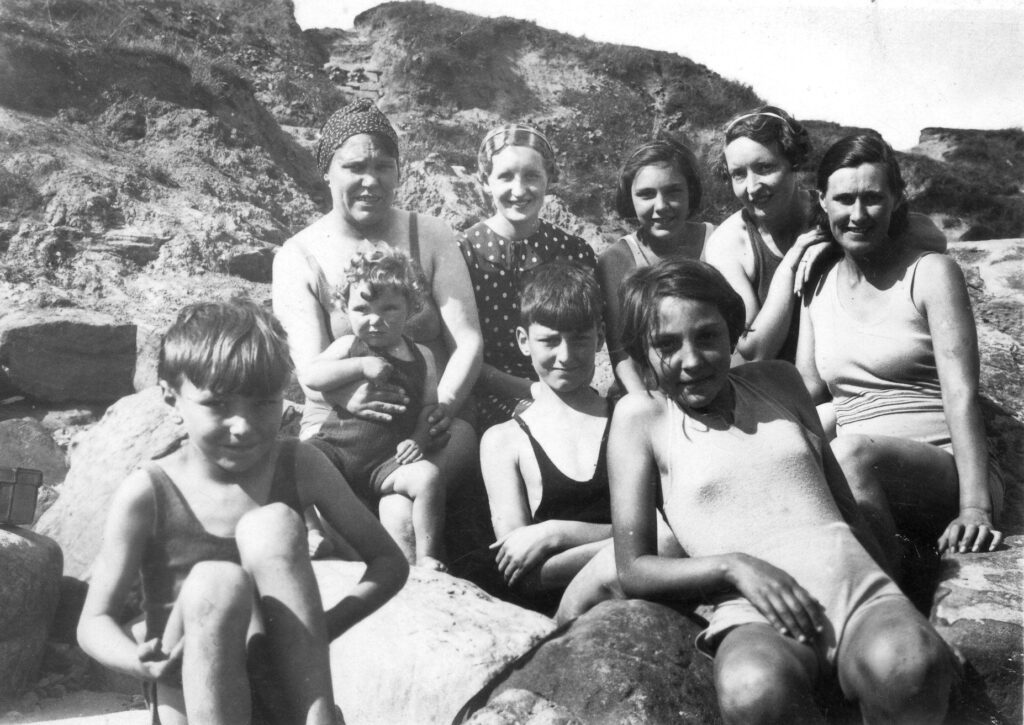

In Greenbelt, Lewis is known for being an Outstanding Citizen, former News Review board member and, for many years, president of GHI, but she was only 4 years old when war was declared in September of 1939, and was the second youngest of a typical large East London family with seven children.

The Blitz lasted from September 7, 1940, to mid-May 1941, leaving a million houses destroyed or damaged in London and 40,000 people, many of them civilians, dead. The bombing didn’t stop then but diminished, only to be followed by the V1 and V2 rockets later in the war.

Sylvia’s War

The News Review was curious about Lewis’ experiences living only five miles (as the bomber flies) from Stepney Green, where the movie is set.

Her home suffered bomb damage and the house immediately behind hers took a direct hit one night when she and her family were sheltering in the cellar. Her elementary school (catty-corner to her home) was flattened and the school she was moved to was in turn bombed out. When she came home vomiting after a tainted lunch at her third school (housed in a church), her parents sent her to school with two “older ladies” who were teaching a small group of children in their home.

Bomb Shelters

When the bombs started falling, she and her brother slept every night in the cellar, under the stairs, where the house framing provided the most protection. They had an Anderson Shelter (made of a curved piece of corrugated iron buried under a layer of soil) at the bottom of the garden but felt safer in the house.

This contrasts with the movie, which emphasizes the public shelters that were eventually opened at Underground stations – a realistic difference because Stepney’s housing was closely packed and often without a basement or yard so public facilities were essential. Lewis’ East Ham home was a couple of steps upscale: still rowhouses but with small front and longer back gardens. Lewis notes that her mother was afraid of the public shelters because of possible molestation so the family never went to one.

When the air raid sirens went off during the school day, children were marched (NO running) to the air raid shelters built on school grounds – long tunnel-like shelters with benches along the length of each side. In the shelters, the teachers led communal singing and comedy acts performed by the children.

Lewis also noted (and the movie does too) that the radio was an important element to home life. The nine o’clock news with Alvar Liddell was a must-listen and at 8 p.m. a nightly radio variety or comedy show drew a wide audience – generating many catch phrases that survived long after the war was over.

Bomb Damage

Lewis’ mother, Rita Kelsey, wrote of the family’s experience of being bombed in 1941. She describes the night of the attack as they sheltered in the cellar, “It was impossible to sleep … as there was not a clear five minutes from either AA barrage, bombs, from 9 p.m. to 5 a.m. So, we took it in turns to sing to drown the racket.” She continues, “Around 2:30 a.m. our roof sailed away with the remaining windows and doors, etc. so I sang all the louder.” When someone suggested a “nice cup of tea” she went upstairs (with the raid still going on) and “groped around in the dark and made an extra big pot.” The next morning, Kelsey saw that the majority of houses all around them were uninhabitable. She says that nearly 600 men had been sent in to repair the homes and that “one by one they were filling up again.”

Kelsey also recounts that the only flowers in the garden were on the earth over the air raid shelter. Everything else was vegetables or space for “22 chickens and 14 rabbits.”

Relating to the Movie

Lewis could not relate the movie to her own reality. She wasn’t part of the night-time exodus to the Underground station and she felt that the movie had a surreal, Dickensian and very dark view of how life was and that reality was sacrificed to caricatures – particularly the looters – and that there was little nuance in the overall picture presented.

The movie does weave in tragedies of the time – a West End nightclub in 1941 that was in full swing when it was bombed and looted and the tragic flooding of Balham Underground Station in 1943 when a bus fell into a bomb crater, severing gas and water mains and drowning people in the tunnels below. Dramatic license, of course, allows these inclusions but Lewis felt that it was overdone and that the result was a frenetic and unrealistic addition to a reality sufficiently poignant on its own.

Lewis hoped the movie would show more of ordinary life – how the sense of normalcy was retained and how life went on despite the disruption. Though there were some scenes of domestic tranquility, singsongs and shared moments of quiet and listening to the radio as a family, she felt that these were swamped by reprehensible behavior: looting, racism and exploitation that were not the norm.

Perhaps the fairest comment is that it’s a movie – and nobody should confuse it with reality.

(With thanks to Sylvia Lewis for sharing her family’s history. There was so much more that could be told of an ordinary family living a life in the target zone.)