Not much is known of the personal histories of the enslaved African Americans who lived and worked on the farms and plantations that now are Greenbelt. Their family relationships are hard to trace over time, because in most records enslaved people were identified only by their first names. There is one such family from Greenbelt, however, whose history can be traced. They were the Waters family: Vachel and Flora Waters and their children. Vachel and Flora met while enslaved in Greenbelt but gained their freedom here too.

Two unusual circumstances make it possible to trace the Waters family history. One is that both Vachel and Flora were uncommon first names that stand out in county records before their family surnames were ever recorded. The second is that their enslavers became their emancipators as well. It was only after they and their children were freed early in the 19th century that their surnames were finally entered into the public record, enabling us to go both forward and backward in time to reconstruct their family history.

The key to unlocking their family history was found in the District of Columbia’s Register of Free Negroes, a record created to serve as proof for free Blacks that they were indeed free, not enslaved. Five siblings named Waters registered between 1827 and 1831, two of whom were explicitly identified as children of Vachel and Flora Waters. Testifying on their behalf was a white man named Benjamin K. Morsell, a merchant, judge and politician in Washington who had a country home in Greenbelt (Montebello, near the water tower).

The involvement of Morsell suggested the Waters family’s Greenbelt connection. The proof of that was found in the probate records of Samuel Turner, whose family cemetery is preserved on Ivy Lane. He lived at Turner’s Discovery, along Ridge Road, just east of Morsell’s home. He conditionally emancipated “Vachal” in his will in 1801. The relevant provision reads: “I bequeath to my wife Susanna … my Negro man named Vachal for the term of eight years and then to be free.” Turner’s subsequent estate inventory listed both a Vachel (age 24) and a Flora (no age given), almost certainly the same couple with the surname Waters named years later in the D.C. records.

It is fair to ask what moved Turner to emancipate Vachel. We can only speculate. Turner was a Methodist, a denomination which at that time was intensifying its opposition to slavery. Also, the labor-intensive tobacco economy was on the wane in northern Prince George’s County. Slave labor was not needed for the crops replacing tobacco. Turner’s estate inventory, in fact, listed no crops at all. He raised livestock and operated a blacksmithing business. Whether it was a sense of justice, religious conviction, economic realism or something else that caused Turner to free Vachel Waters is lost to history.

How did Vachel and Flora Waters come to the Turner household? The documentary record is clear for Flora, less so for Vachel.

Flora came to Greenbelt from the household of John Chew Thomas, a former Congressman. Thomas’ wife Mary Snowden inherited part of Snowden’s Discovery, a sprawling tract of land in Greenbelt. They already had a home in Anne Arundel County, so they sold off Snowden’s Discovery in several parcels. The buyer of one of the parcels in 1800 was Turner. Along with the land, Turner and his wife Susanna hired Flora from Thomas. Flora was “in possession of the widow Turner” (though still owned by Thomas) when Thomas emancipated her and her four children by a deed of manumission in 1810. So the evidence indicates that Vachel and Flora met in the household of the Turners of Greenbelt. Whether Thomas emancipated Flora in 1810 in response to Vachel’s emancipation is not known. He conditionally emancipated more than 30 other enslaved men, women and children at the same time. Religion might have played a role, for he was a Quaker, another anti-slavery sect.

Vachel’s path to the Turners was less direct. It started at Jericho, a tobacco plantation on the Patuxent River near old Bowie. Jericho was owned by John Waters (1698-1774), one of the largest slaveholders in northern Prince George’s County. When his estate was inventoried, 12 enslaved people were named, including a man named Vachel (age 21) and a woman named Rachel (age 19). Rachel’s name next appears 11 years later (age 30) in 1786 on the estate inventory of Waters’ daughter Mary Waters Williams. A widow who owned no land herself, Mary seems to have lived her later years on the upper reaches of Beaverdam Creek in what is now the Beltsville Agricultural Research Center, where her adult sons owned plantations. Besides Rachel, four enslaved children also appeared on Mary’s estate inventory. The oldest was named Vachel (age 8). He most likely was the same 24-year-old Vachel on Samuel Turner’s inventory 16 years later. Why he moved from the Williams household to Turner’s is not known, but the families knew each other. Williams’ son John was a partner with Samuel Turner in the blacksmithing business.

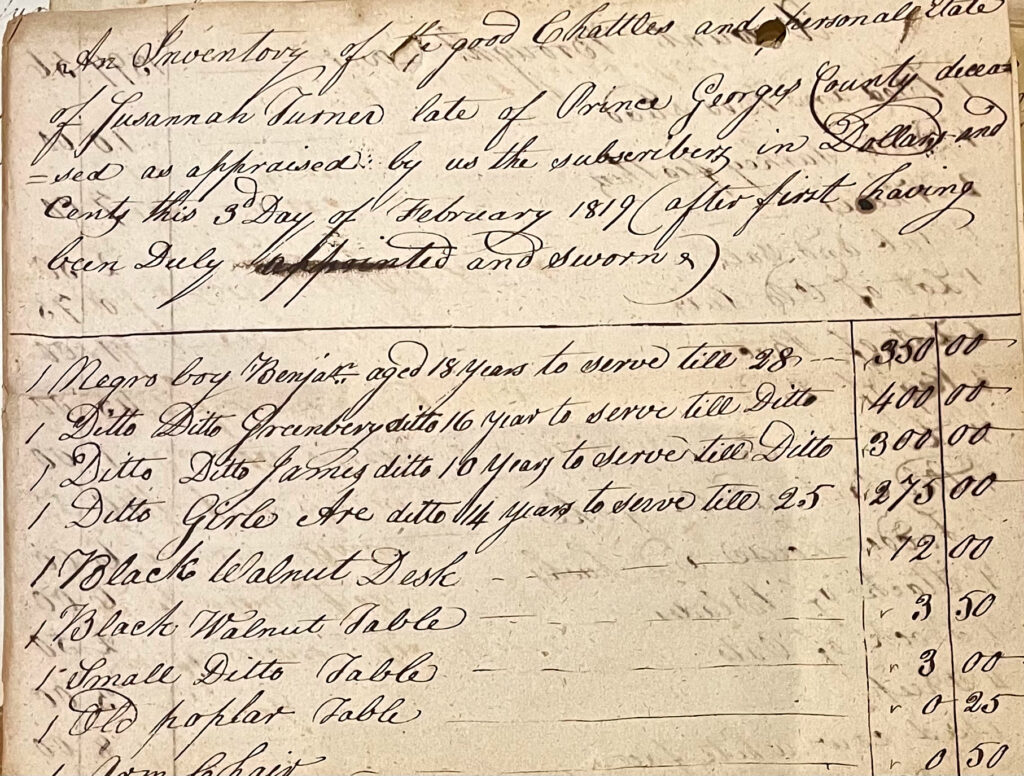

The Waters family story is not as simple as a family enslaved and then freed. Vachel and Flora had four children before they were emancipated, meaning those children were born into slavery. John Chew Thomas emancipated Flora immediately, but he set conditions on her children’s freedom: her boys Benjamin, Greenbury and James at age 28, daughter Ariana at age 25. So even though Vachel and Flora became free in 1809 and 1810, their four eldest children (all then below the age of eight) were not. When Susanna Turner died in 1819, they were listed on her estate inventory. When her estate was liquidated, their remaining terms of service were purchased by Susanna’s children and their neighbor Benjamin K. Morsell. From the D.C. Register of Free Negroes we know that Vachel and Flora had at least two more children born after they became free, Peter and Elizabeth. Those children, unlike their older siblings, were thus born free. The household was a mixed one of both free and enslaved members.

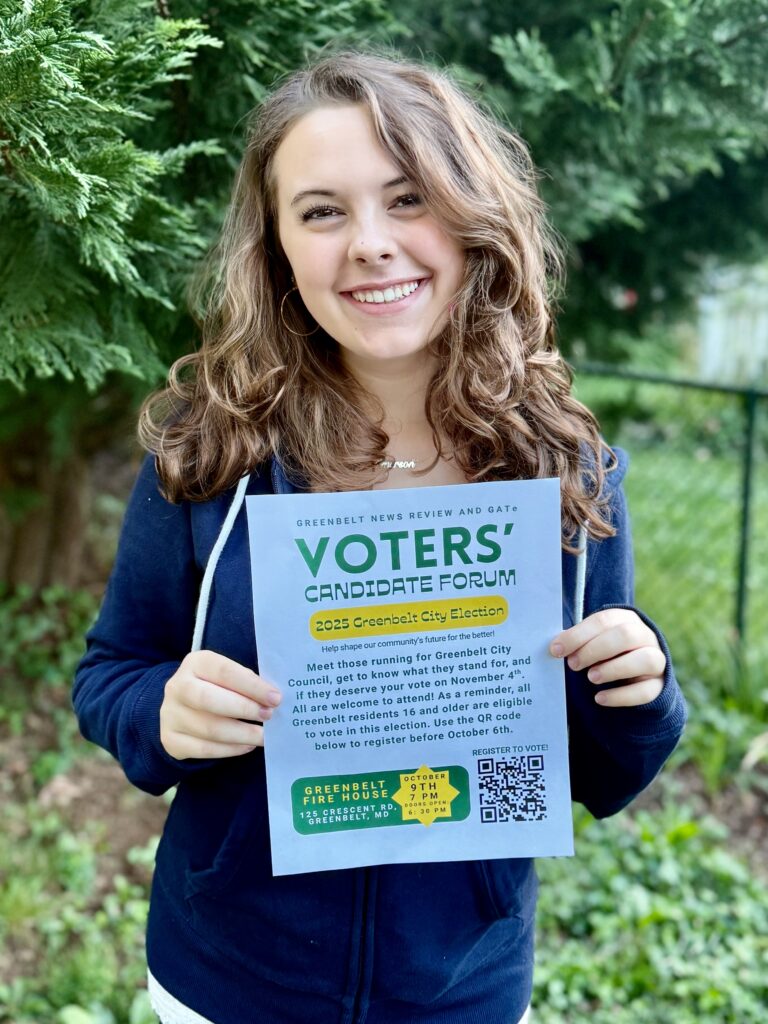

Five of Vachel and Flora Waters’ children relocated to Washington, D.C. The child whose life is best documented is their eldest daughter Ariana (usually called Airy), born enslaved. Her term of servitude did not end until about 1830, when Morsell vouched for her free status. Her freedom certificate reads: “Airy was born the property of Susanah Turner of Prince George’s County, Maryland, with whom she served until Turner’s death [1819], and then was purchased by Morsell. She has finished her time of servitude in Washington with Morsell and is free.”

By then Ariana was married to a man named William Dodson and her name was Ariana Dodson. She appears as a free woman and the head of a household in the 1840, 1850 and 1860 censuses for the District of Columbia. In the 1862 Washington city directory she is listed as the widow of William Dodson, occupation washer woman. An older woman named F. Waters was living with her in 1850, possibly her mother Flora from Greenbelt. No further record of Ariana has been found after 1862. The stories of Vachel and Flora Waters’ other children have not yet been traced.

The Waters family story in Greenbelt and Washington is far from complete. We know nothing of their inner lives, their hopes, fears, joys, heartbreaks or aspirations. But the fragmentary details that have been recorded present a glimpse into the lives of an enslaved African American family whose paths to freedom were set in motion in Greenbelt.