A tea cup? A salt spoon? A wine glass?

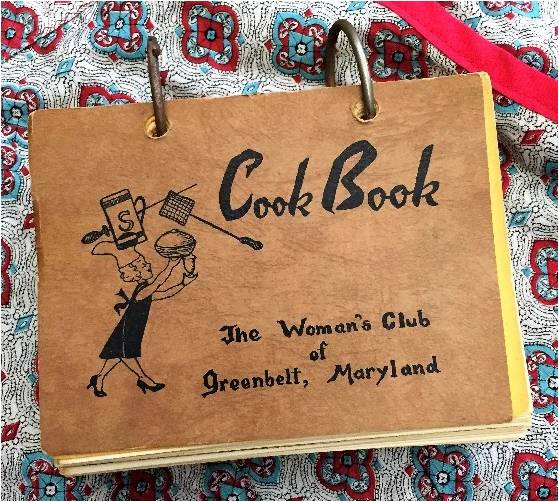

These are just a few of the frustratingly unspecific cooking measures highlighted by Kara Harris in her virtual lecture, Exploring Maryland’s Historic Cookbooks, at the Greenbelt Museum on Thursday night, July 21. Introduced by Museum Director Megan Searing Young, Harris mentioned that she was excited when, at a recent visit to the Greenbelt Museum, she saw some books in their collection that she had been interested in for a long time. A particular treasure is a historic Maryland cookbook published by the Woman’s Club of Greenbelt, probably compiled in the 1950s. Culinary historian and blogger Harris, a Beltsville native, has become well known in the state and nationally through her Old Line Plate blog (oldlineplate.com). On her site, she not only describes her deep dives into old Maryland cookbooks, but she also tests historic recipes and shares them online. Her source materials include old handwritten recipes, cookbooks and recipes from newspapers she has discovered in libraries and archives across the country. Along the way, she explores social history through documented accounts of many of the recipe authors. “Even what people want to project with these recipes can be interesting – their wealth, their thrift, their skill,” said Harris.

She began her lecture by noting that, although cookbooks and recipes have been around for centuries, there was a boom in published cookbooks in the 1800s. Social changes, an interest in domestic science and family nutrition were likely all drivers of this trend. An important landmark of this era was the publication in 1896 of Fannie Farmer’s The Boston Cooking-School Book. In her recipes, Farmer first popularized the idea of using standardized measurements – from the rather vague “tea cup” to a measuring cup that equals 8 ounces, for instance. Harris pointed out that publishing cookbooks was also simply “a neat thing to do”: “Think about social media showing off pictures of what we eat,” she said. “That’s what a lot of these books were like: hundreds, sometimes thousands of recipes.”

“I also love community cookbooks. They all have their own personalities; people would add their own recipes in the margin. Every church cookbook is a historical document full of names, people who have backstories and recipes that reflect changing times. The women who produced community cookbooks were very marketing savvy,” Harris pointed out. “They sold ads to local businesses and they also incorporated new ingredients – essentially, product placement.” For instance, baking powder was a revolutionary new ingredient in the 1800s, “and people had to learn how to use it.”

“The advertisements in some of the Maryland cookbooks are sometimes the most interesting part. Some local books have a lot of ads that demonstrate a whole neighborhood’s worth of local businesses at the time the cookbook was printed,” explained Harris. “It’s like a phone book – you get a window into what kind[s] of goods were available or how or why they are being advertised in the first place.” For example, ads for grocers indicate where women might shop or ads for appliances show what would be cutting-edge kitchen equipment at the time.

At the end of her lecture, Harris invited the audience to send her their recipes to share on her blog and to explore her database of more than 50,000 recipes that she has digitized from various sources. “If you are a cook who improvises, how do you write down that process? By writing down [your recipe] you’re deciding the one way, the best version of your recipe,” she said. “Who knows? Maybe one day your vision could become the only authentic way to make that dish.”