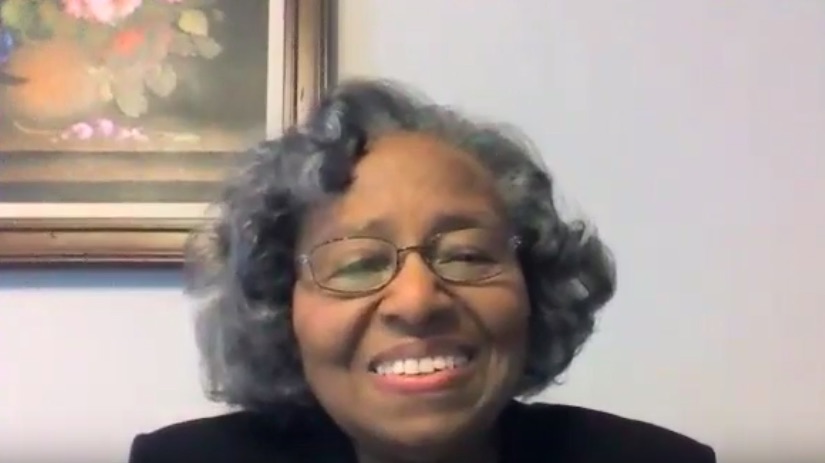

Angie Bass Williams and her husband Rivers were among the first people of color to live in Greenbelt. On February 25, Angie Williams was interviewed by Councilmember Emmett Jordan, on behalf of the Greenbelt Museum and the Greenbelt Black History and Culture Committee, giving her a chance to recount her and her family’s experience in Greenbelt and Prince George’s County in that seminal period when the nation was just beginning to desegregate as a result of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, among other milestones. While finding Greenbelt a welcoming and open place overall, the Williams family encountered struggles along the way, first in their search for a safe home and neighborhood and in their goal to be part of a community where they were very much a minority.

Williams was born in North Carolina and spent her early years in Newport News, Va. The seventh of nine children, her father was a lay minister, and she graduated from a segregated high school and began studies to fulfill her goal of becoming a stenographer. Her first job was at Fort Monroe, Va., a segregated environment where she was only among a few people of color, including the soldiers on base. She excelled through hard work and a perfectionist approach.

She went on to spend about two years working at the Pentagon as the Vietnam War raged, before transitioning to a more enjoyable stint at the Smithsonian Air and Space Museum, during the period of the then-burgeoning space program.

Throughout, she was active in her Mennonite faith and, over time, became an ordained minister. In her spiritual life, she experienced a rare integrated environment, even as a girl.

After marrying, a bond that has lasted 57 years, she and her husband moved to the D.C. area, because it afforded closeness to both their jobs. Yet, it was their dream to own a home and raise a family in a safe and integrated neighborhood. They eventually settled on moving to Prince George’s County.

What followed was a string of disappointments, as their initial phone calls to realtors, engendering excitement, were followed by discouragement upon a face-to-face meeting, as they were often directed to neighborhoods that were majority African American, areas that, at the time, were known for high crime rates. When they came up against the reality of racial segregation, they realized that it was naïve to think that simply being able to afford a house meant success in buying one.

Citizens for Fair Housing

Eventually, however, the Williams were referred to the Greenbelt Citizens for Fair Housing, who were able to assist them in finally purchasing a home in the environment they were seeking. On February 12, 1966, they moved into 7-H Southway in the Greenbelt Homes Inc. housing cooperative, remaining there until November 1968. Later, they would move into a larger home more conducive to a growing family in Boxwood Village.

Williams said they “loved” their Greenbelt experience, never feeling unsafe or persecuted, and enjoyed the many cultural activities. What they did experience at times was the feeling of being an object of notice, where many seemed to know a great deal about them without really knowing them personally. Williams recounted the difficulty of finding babysitters for their child when the color of their skin became known. Outside of Greenbelt, the county at the time was a mixed bag of troubled and safer areas and the Williams had to pick carefully in their social outings. The Williams made a point of making diverse friends, most especially Bert and Marjorie Donn, and being active in the community. They hosted gatherings at their home and had many visitors over the years.

The Williams left Greenbelt in the 1970s for a time, returning in 1988 to see their younger son, who excelled at football and scholastics, graduate from Eleanor Roosevelt High School.

Williams said that they wanted to “teach their children the value of all people,” that they all are “God’s creation.” Their life in Greenbelt afforded them this opportunity.

Jordan pointed out that while Greenbelt was built by both African American and white relief workers, it remained an all-white community for decades. He said that while much has changed for the better, census data show that both the county and city retain some of the segregated housing patterns that are the vestiges of a much more divided past.